Home » Resources » UXO City Guides »

UXO City Guide

Home Office Bombing Statistics for Dover

Record of German Ordnance dropped on the Metropolitan Borough of Dover

High Explosive Bombs (All types)

365

Parachute Mines

1

Oil Bombs

3

Phosphorus Bombs

2

Fire Pots

1

Pilotless Aircraft (V-1)

3

Long-range Rocket Bombs (V-2)

0

Weapons Total

375

Area Acreage

4,447

Number of items per 1,000 acres

108.8

Why was Dover targeted and bombed in WWII?

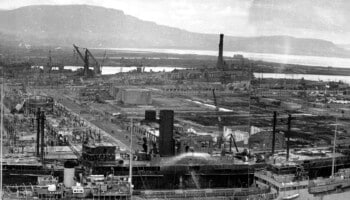

The town of Dover played an essential role during WWII. Its position meant it was very much on the ‘front line’ of attention from the German military. It was an easy and very reachable target for both the Luftwaffe and for the cross-channel German gun batteries on the north coast of France. At the start of WWII in 1939, the Admiralty took control of the port of Dover transforming the harbour into a naval base, making it a very viable target.

Dover also played a crucial role in Operation Dynamo, being the focal point of the evacuation of Allied soldiers from Dunkirk, France, in the summer of 1940. Dover Castle’s network of secret tunnels became the headquarters of the operation, which saw more than 338,000 personnel rescued from northern France.

The bombing and shelling of Dover resulted in 3,059 air-raid alerts, 216 civilians killed and 10,056 properties damaged. A network of caves and tunnels were located within the cliffs and were regularly used as air-raid shelters and as a military base. Dozens of anti-aircraft guns were installed along the coast, along with some massive naval guns with the ability to reach. Some of the military targets identified by the Luftwaffe in the area are shown in the 1940 reconnaissance photograph below.

Home Office Bombing Statistics for Dover

Dover was not as heavily bombed as Britain’s larger cities, nevertheless it sustained an overall moderate bombing density.

Details recorded by official Home Office bombing statistics highlight the quantity and type of bombs that fell on the Metropolitan Borough of Dover during WWII. A total of 375 recorded bombs fell on Dover, equating to 108.8 items of ordnance per 1,000 acres. Interestingly, the statistics exclude projectiles for which around ninety were recorded via alternative sources.

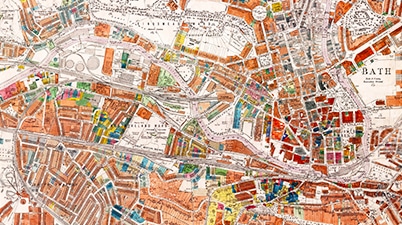

Bombing and shelling was largely concentrated on the town centre. The map below shows the high concentration of incidents, which left few areas of the town unaffected.

However, additional bomb maps obtained from the National Archives highlight that the bombing of Dover was not restricted to the harbour area – with reports of bombs being dropped well into the city’s outskirts.

Major bombing raids in Dover

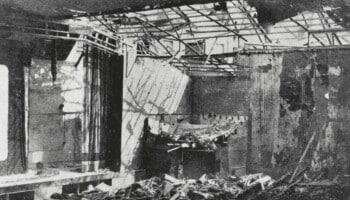

Few places in Dover were left unaffected by bombing. The first bombs fell on the town on 6th July 1940. The density was bomb and shell strikes on Dover town centre was said to be higher than the density in central London – and the attacks were almost daily.

Dover became a symbol for Britain’s wartime bravery and found itself at the centre of East Kent’s ‘Hellfire Corner.’ 1940 saw the worst of the bombing, with significant incidents on Matthews Place, Noah’s Ark Road, Peter Street, Edred Road, St. James Street, Harold Street, Clarendon Street, Manor Road, Connaught Park and Norman Street.

Bomb damage led to widespread evacuation, the population of the town dwindled from more than 40,000 in early 1939 – to an estimated 16,500 in 19401. Somewhat countering the outflow, hundreds of military personnel were billeted in the town to operate the cross-channel guns and extensive anti-aircraft defences.

The WWII Shelling of Dover

Following Germany’s victory over France in June of 1940, Hitler ordered his military engineers to erect a network of batteries for some of the Third Reich’s biggest guns along the French coast at Cap Gris-Nez. The German military hoped the weapons would close the sea-lane of the English Channel to Allied shipping, but Hitler also planned that his gun emplacements would provide fire support for a future cross-channel invasion of the UK.

Soon, the area around Calais was covered with guns. Nearly twenty pieces were added to six batteries running from Boulogne-Sur-Mer eastwards towards Calais and beyond. The guns ranged in size from comparatively “light” eight-inch cannons capable of ranges up to 33km, to massive 16-inch radar-controlled weapons, which could fire one-ton projectiles more than 50km. At the height of the bombardment, nearly 75 high-calibre weapons were trained onto England’s southern coast.

For the next four years, the German military subjected the Dover Strait and the Kent countryside to a battering of artillery. Shell fragments were found as far as Chatham, Kent, about 88km (55 miles) from the French coast. At least 1,000 attacks were recorded in just over four years.

Dover, which is easily observed from the French shoreline, bore the worst of it. Between August 1940 and September 1944 2,226 shells landed on the town and 686 in the surrounding areas. Hundreds more burst in the air or landed in the harbour2. Up to 10,000 buildings in and around the city were damaged by shellfire and more than 200 civilians were killed with hundreds more injured3.

The final shell fell on Dover in September 1944, after which the guns at Calais were captured by advancing Allied forces.

Can UXO still pose a risk to construction projects in Dover?

The primary potential risk from UXO in Dover is from items of German air-delivered ordnance that failed to function as designed.

Approximately 10% of munitions deployed during WWII failed to detonate, and whilst authorities did search for related items, not all were encountered during the immediate post-war period. This is evidenced by the regular discoveries of UXO across the UK – not just in Dover.

Another risk in the Dover area is encountering British/Allied unexploded ordnance remaining near WWII military landmarks. The clearance of ordnance from military camps, depots and barracks was not always effectively managed – and search and detection equipment used at the time were often ineffective. Notable military camps within Dover included those at Eastern Heights, Western Heights, Dover Old Park and the Connaught Barracks – with numerous explosive ordnance clearance (EOC) tasks being undertaken around the Dover Castle area.

I am about to start a project in Dover, what should I do?

Developers and ground workers should consider this potential before intrusive works are planned, through either a Preliminary UXO Risk Assessment or Detailed UXO Risk Assessment. This is the first stage in our UXO risk mitigation strategy and should be undertaken as early in a project lifecycle as possible in accordance with CIRIA C681 guidelines.

It is important that where a viable risk is identified, it is effectively and appropriately mitigated to reduce the risk to as low as reasonably practicable (ALARP). However, it is equally important that UXO risk mitigation measures are not implemented when they are not needed.

While there is certainly potential to encounter UXO during construction projects in Dover, it does not mean that UXO will pose a risk to all projects. Just because a site is located in Dover does not mean there is automatically a ‘high’ risk of encountering UXO. It really does depend on the specific location of the site being developed.

A well-researched UXO Risk Assessment will take into account location specific factors – was the actual site footprint affected by bombing, what damage was sustained, what was the site used for, how much would it have been accessed, what were the ground conditions present etc.

It should also consider what has happened post-war – how much development has occurred, to what depths have excavations taken place and so on. This will allow an assessment of the likelihood that UXO could have fallen on site, gone unnoticed and potentially still remain in situ.

Recent UXO discoveries in Dover

Since the war, many items of UXO have been discovered across multiple cities within the UK, with Dover no exception. See the news articles below about UXO incidents and discoveries from national and local press in Dover.

1st Line Defence keep up-to-date with relevant and noteworthy UXO-related news stories reported across the UK, and you can browse through these articles using the buttons below.

Get UXO risk mitigation services from a partner you can trust

UXO City Guides

Got a project in Dover? Need advice but not sure where to start?

If you need general advice about UXO risk mitigation in Dover, contact us and we will be happy to help.

Contact Us

* indicates required fields